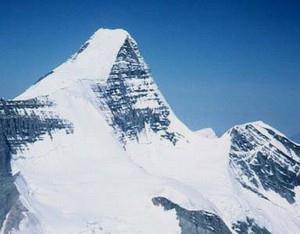

Photo: Looking south-southeast to Mount Robson (courtesy Dr. John D. Birrell)

Mount Robson

- 3954 m (12,973ft)

- First Ascent

- Naming History

- Hiking and Trails

Located in the Fraser River Valley east of the Robson River; 4 km south of Berg Lake

Province: BC

Park: Mount Robson

Headwater: Fraser

Major Valley: Fraser

Visible from Highway: 16

Ascent Party: W.W. Foster, Albert H. MacCarthy

Ascent Guide: Conrad Kain

Named for: Robertson, Colin (Colin Robertson was an employee of both the Hudson Bay Company and the Northwest Company during the early 1800's. See details below for a complete discussion of the naming of Mount Robson.)

Journal Reference: CAJ 6-11,19

"Mount Robson is not only the highest mountain in the Canadian Rocky Mountains but one of the great mountains of the world, and deserving of inclusion in any select list on account of many striking characteristics and a form, beauty, and grandeur transcending any other of the greater peaks of the Rockies… The mountain is unique, and its massive precipices, seamed with different-coloured rock strata, enhance it in both beauty and stature." These words were written by Frank Smythe, an English mountaineer who wrote dozens of books about the mountains of the world during the first half of the twentieth century and was widely regarded as an authority on the subject. The first to write about this view were William Fitzwilliam (Viscount Milton) and Dr. Walter Cheadle who reached this location in 1863. Although much less knowledgeable about the mountains of the world, they were obviously very impressed as well, writing, "On every side the snowy heads of mighty hills crowded round, whilst, immediately behind us, a giant among giants, and immeasurably supreme, rose Robson’s peak. This magnificent mountain is of conical form, glacier-clothed, and rugged. When we first caught sight of it, a shroud of mist partially enveloped the summit, but this presently rolled away, and we saw its upper portion dimmed by a necklace of light feathery clouds, beyond which its pointed apex of ice, glittering in the morning sun, shot up into the blue heaven above, to a height of probably 10,000 or 15,000 feet. It was a glorious sight, and one which the Shuswaps of the Cache assured us had rarely been seen by human eyes, the summit being generally hidden by clouds." In 1911, from a ridge below the summit of Lynx Mountain, Arthur O. Wheeler enjoyed his first view of the Mount Robson area. He later wrote, "As we topped the crest the whole wonderful panorama came into view. At our feet flowed the Robson Glacier.Across the wide river of ice the great massif of Robson, rising supreme above all other peaks. White against a sky of perfect blue it seemed to belong to a world other than our own. Ethereal, snowy Resplendent Mountain, crowned with immense sculptured cornices; the splendid sharp conical peak Whitehorn Mountain; it was the most stupendous alpine scene I had ever gazed upon, setting the blood coursing though the veins as fast as a torrent, with the pure joy of being alive -and there." At the end of the final volume of the Interprovincial Boundary Survey Report and after studying the Continental Divide from the US border to 120 degrees longitude, Arthur Wheeler wrote of the view from Robson Pass, "In no other pass of the Rockies does one mountain so dominate the entire landscape as does Mount Robson. Its enormous mass towers 7532 feet above the summit of the pass at such close range as to literally over-shadow it. Together with Robson Glacier, curling around its easterly face, Mt. Robson completely fills the range of the eye’s vision. It constitutes a picture of such unique character that it will probably become world-famous among artists as an outstanding example of a tremendous, solitary, self-contained subject in black and white, in the boldest style imaginable." No convincing is required to have us believe that Mount Robson is the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies as it towers above the Fraser Valley and the neighbouring peaks. Clearly the most impressive thing about this view of Mount Robson is the height of the peak above the Fraser River Valley. The mountain has an elevation of 3954 metres, 200 metres higher than Mount Columbia, the second highest. Combining with this, our viewpoint is at a relatively low elevation of only 825 metres. So from the Swiftcurrent Creek Bridge Viewpoint we are looking up 3129 vertical metres to the summit. No other view in the Rockies even approaches this "base to peak" statistic. Coleman, a geologist who was one of the first visitors to the area, observed that Mount Robson is located at the base of a gentle syncline. He speculated that, "the 'slightly compressed and therefore strengthened parts of the syncline" may have better resisted erosion than the "more expanded and shattered forms around it, once probably parts of anticlines." As a result of this, the prevailing westerly winds must achieve a tremendous vertical rise to pass over the massive mountain and so, regardless of weather in the valley below, the summit is often obscured in clouds For this reason the peak was referred to by some early as “Cloud Cap Mountain.” The height to which the winds must rise to pass over the summit results in two other remarkable features of the mountain. Below its southwestern cliffs, particularly heavy levels of precipitation result in a very unique forest. As well, the moisture laden air tends to deposit a series of teeth like pinnacles across the summit crest which may be seen from the highway under good viewing conditions. From the Swiftcurrent River Bridge on Highway #16 Mount Robson is a massive, somewhat symmetric peak with two broad shoulders. Their numerous thin layers are highlighted by partially melted snow in mid and late summer. A glacier flows between the summit and the south shoulder which has been named The Dome. Descending from just below the summit, a long, steep, and often snow-filled couloir descends to the valley of the Robson River. On the hidden side of the mountain lies one of the most impressive glacier systems in the Rockies and it is from this point that most mountaineers attempting the peak begin their climbs. But there is no easy route up this mountain and this, in combination with the weather on the mountain results in few successful ascents. Conrad Kain, who is honoured by a peak to the southwest of Resplendent Mountain, wrote of the mountain, "In all my mountaineering in various countries, I have climbed only a few mountains that were hemmed in with more difficulties. Mount Robson is one of the most dangerous expeditions I have made. The dangers consist in snow and ice, stone avalanches, and treacherous weather." The Shuswaps are said to have referred to Mount Robson as The Mountain of the Spiral Road because of its distinctive, horizontal layers of rock which angle upwards to the east, giving the appearance of a track running around the mountain to form a spiral. An article in the 1970 Canadian Alpine Journal by T. Gardiner summarizes the possible sources of the name Mount Robson. The most plausible explanation seems to be as follows: The first written reference to the name “Robson” occurred in the journals of Milton and Cheadle who crossed Yellowhead Pass in 1863. They referred to the peak as “Robson Peak” and “Robson’s Peak.” In the early years of the nineteenth century, the North West Company outfitted parties to hunt and trap in the mountains near the Athabasca River. One party was led by a man whose name was “carelessly pronounced” and had a camp near what is now known as Mount Robson. This was likely Colin Robertson (1783-1842) who worked for both the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company around 1815. The spot became a gathering place for the various parties of hunters and the peak was named after him. The first written reference to the name is by George McDougall, a fur trader, in his diary of 1827. He wrote of a location known as “Tete Jaune Cache”, a place where an Iroquois Indian half-breed who was fair haired had made a fur cache, or a place to store his catch of furs. He was known as Tete Jaune or Yellowhead. McDougall wrote that it was, “near the meeting of the Grand River –which flows from the base of Mt. Robinson –and the Fraser River.” The first step in the transformation of the name seems then to have been from “Robertson” to “Robinson.” Between 1827 and the visit by Milton and Cheadle the name was further transformed from “Robinson” to “Robson.” There are other possible explanations for the name and the above-mentioned article by T. Gardiner should be referred to for a complete summary. THE FIRST ASCENT OF MOUNT ROBSON "Oh what a glorious sight he was that day we first saw him. There, buttressed across the whole valley and more, with his high flung crest manteled with a thousand ages of snow, Mount Robson shouldered his way into the eternal solitudes thousands of feet higher than the surrounding mountains." This was George Kinney’s reaction in 1907 to his first view of the mountain that entranced him and was the focus of his life for the next four years. Kinney was born in New Brunswick, had investigated the fossil beds on Mount Stephen and completed a solo ascent of that high mountain in October of 1904. A founding member of the Alpine Club of Canada, Kinney joined Arthur and Quincy Coleman on what was the first expedition to attempt to climb the highest mountain in the Canadian Rockies. Arthur Coleman had spent several years searching for the legendary Mount Brown and Mount Hooker which had been touted have elevations of about 5000 metres only to find that a "mistake" had been made. Understandably, he was concerned that this peak, which it was claimed rose over 3000 metres above its base, might be grossly exaggerated as well. The trio left Lake Louise and after struggling through burnt timber and wilderness for forty-one days reached the base of the mountain. Unfortunately the weather was bad and as they were too late in the season, they were only able to explore the base of the peak. Kinney and the Colemans returned again in 1908 and after two attempts were abandoned in bad weather, Kinney set out on a solo attempt on September 9th, ovenighting in bad weather and reaching an elevation of 3200 metres before avalanches drove him off the mountain. The following day the trio reached 3500 metres in fine weather before retreating. The Colemans and Kinney made arrangements to continue their efforts the following year. However following reports that a "foreign" party (Arnold Mumm, Geoffrey Hastings, Leopold Amery, and Moritz Inderbinen) had eyes on the peak, Kinney set out earlier in the season than planned, alone, "hoping to pick up someone on the trail to share fortune with me." The Athabasca River had reached very high levels and both Curly Phillips and George Kinney had been marooned on islands for a few days before their chance meeting at John Moberly’s cabin above Jasper Lake on July 11th. Curly Phillips had also entered the mountains by himself, hoping to start an outfitting business. Even though Phillips had never climbed a mountain, Kinney thought the, "blue-eyed, curly headed clean-lived Canadian" was, "perfectly fit for the undertaking I had in hand." Fourteen days later they reached the base of Mount Robson. Twenty days of bad weather greeted them although they made three attempts, spending one night on the mountain at 3050 metres. Finally, with their provisions nearly depleted, a clear day dawned. This would be George Kinney’s twelfth attempt. After overnighting again on the mountain, they may have believed that they reached the summit ridge, now known as Emperor Ridge, on August 13th in dense clouds, cold, and high winds. The ascent was a tremendous effort over steep rock, ice, and snow. Curly Phillips had no prior mountaineering experience and did not even have an ice axe, using instead a stout pole from the forest below. They had ascended the immense northwest face of the mountain.This was the most direct way to the summit but has probably never been climbed since as there are several safer and better mountaineering routes on the peak. In 1913 a team of experienced climbers organized by the Alpine Club of Canada journeyed to the peak under very different circumstances than those endured by George Kinney during his attempts. The group was able to travel to the base of the peak by railway and then to their base camp at Berg Lake beneath the mountain’s northern cliffs by pack train under the guidance of Curly Phillips himself. Conrad Kain, an Austrian guide who had a well-established reputation with the Alpine Club, was to lead two experienced mountaineers, Albert MacCarthy and William Foster. The route Kain had chosen was on the northeast side of the mountain and was quite different to that climbed by Kinney and Phillips in that most of it was on ice. According to the club’s official records, "Thirteen hours of strenuous fighting up rock cliffs and dangerous slopes of snow and ice, where sixteen hundred steps had to be cut with the ice axe, brought them to the summit at 5 o’clock in the evening." Kain later wrote that, "Mount Robson is one of the most beautiful mountains in the Rockies and certainly the most difficult one." Controversy continues to this day as to whether or not Curly Phillips and George Kinney reached the summit ridge or even the highest point on the ridge. Kinney is quoted as stating, "We finally floundered through these treacherous masses and stood, at last, on the very summit of Mount Robson." Curly Phillips is reported to have confided to William Foster that he and Kinney, "didn’t get up that last dome (of sixty feet)." Some suggest that Arthur Wheeler and the Alpine Club of Canada pressured Curly to say that they had not reached the actual summit in order that the 1913 expedition could claim credit for the first complete ascent. In his book, "Pushing the Limits," mountaineer and historian Chic Scott thoroughly reviews all aspects of what is one of the few genuine controversies in the history of Canadian climbing. He makes it clear that he is a great admirer of the efforts put forth by Kinney and Phillips but in the course of his research Chic appears to have produced evidence that they did not reach the ridge. There is also evidence that they may have reached a spot that they could have mistakenly taken to be the summit under poor visibility conditions. Chic's detailed analysis is documented in his book and again in the ACC 2001 Journal. What is clear is that the perseverance and courage demonstrated during the climb by George Kinney and "Curly" Phillips is one of the most outstanding achievements in the mountaineering history of the Canadian Rockies. Conrad Kain maintained, "They deserve more credit than we, even though they did not reach the highest point, for in 1909 they had many more obstacles to overcome than we; for at that time the railway...was no less than two hundred miles from their goal and their way had to be made over rocks and brush, and we must not forget the dangerous river crossings." The pole which Curly used on his ascent remains one of the most prized possessions of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies. [Additional information: http://www.digitalbanff.com/spiral/kinney/index.html by James L. Swanson] [Additional information: "Pushing the Limits" by Chic Scott; Page 70]