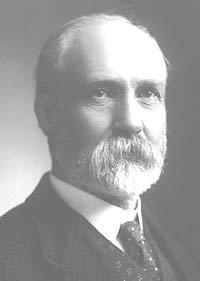

Arthur Coleman (Courtesy Whyte Archives, V14 ACOOP-82)

Arthur P. Coleman

(1852-1939) Born in La Chute, Quebec, Arthur Coleman became Professor of Geology at the University of Toronto who travelled widely in the Canadian Rockies and Selkirks. He completed a total of eight trips major exploratory trips. His brother, L. Quincy Coleman lived in Morley and was Arthur's outfitter for his last five expeditions in the Rockies. In the late nineteenth century the first mountaineers to visit the Rockies were very anxious to visit Athabasca Pass and climb the legendary peaks Mount Brown and Mount Hooker that were touted to have an elevation of at least 16,000 feet by botanist David Douglas. Arthur Coleman wrote, "A high mountain is always a seduction but a mountain with a mystery is doubly so...I studied the atlas and saw Mounts Brown and Mount Hooker...(and) I longed to visit them." Coleman first visited the mountains of western Canada in 1884, reaching the end of the railway at Laggan (Lake Louise). While there, he climbed a small mountain, likely one of the first to do so in this area. He wrote, "It was only a commonplace mountain, about eight thousand feet high, without a name, so far as I am aware; but it belonged to the family of Rocky Mountains, and gave one an introduction to its stately neighbours, for here one could gaze up and down the pass with nothing but clean air between one and the summits, while down in the valley a trail of smoke from the "right of way" (CPR construction) where the timber was burning blurred and sullied the viewƒ Northward, up Bow River, one could see a blue lake at its source (now known as Hector Lake); and across the main valley, with its smoke and bustle, rose several fine mountains with glaciers, and at the foot of one of them beautiful Lake Louise. Following his day climbing in the Rockies, Coleman carried on to Golden and visited the Selkirks. During his return journey, he paused again in the Rockies, this time below Castle Mountain. From there he ascended to camp in "the beautiful Horseshoe Valley behind the Castle" from which he made the first ascent of the mountain. "Above the edge of the cliff, however, going was easy, so that the highest part of the Castle (nine thousand feet) was not hard to reach, and the wonderful view of the valley of Bow River, four thousand feet below, was quite worth seeing. The tower standing in front of the Castle to the south-east looked as unscalable as it was reported to be." Returning in 1885, the railway was still not complete but he was able to travel along its route to Revelstoke. From there he made his way into the Selkirk Mountains. Coleman returning to the Rockies in 1888, travelling by train to the Columbia Valley. After canoeing down the Columbia River he attempted to reach Athabasca Pass from the Columbia River but was unsuccessful due to lack of supplies and the ruggedness of the terrain. In 1892, he again returned to the Rockies, this time accompanied by his brother Quincy, who lived near Morley, Alberta, L.B. Stewart, Dr. Laierd, Mr. Pruyn, and two Stoney guides, Mark Two-young-men and Jimmy Jacobs. Coleman's party had to rely on the native's knowledge of the trails and the mountain passes. He wrote: "One man appeared to have almost reached the point we were aiming for, Joby Beaver, the most enterprising hunter of the (Stoney) tribe, but he made so much money from furs and jerked meat to care to work for a white man; however Jimmy was supposed to have gathered his ideas on the subjects of routes, and it was hoped would find the way through the passes along Joby's trails." They travelled extensively, covering some eight hundred kilometres of the mountains between Morley and the Chaba River before again failing to reach Athabasca Pass. Their route took them up the Red Deer River valley to "Mountain Park" (Ya Ha Tinda) up Scalp Creek and down Skeleton Creek to the Clearwater Valley, up the Clearwater and then over Whiterabbit Pass to the North Saskatchewan River. After travelling down the river they turned north to the Brazeau River, reached Brazeau Lake, travelled through and named Poboktan Creek and Poboktan Pass, "from the big owls that blinked at us from the spruce trees," and reached the Athabasca valley. They then "tramped" to Fortress Lake, climbed "Misty Mountain" (now Brouillard MountainMount ClemenceauJob Pass, Coral Creek, Whiterabbit Pass to the Clearwater River and back to the Red Deer River, and eventually to Morley. This was a most remarkable trip at a time when their party would have been the first non-natives through most of this country but they had not found the legendary Mounts Brown and Hooker. In 1893 Coleman, accompanied by his brother Lucius, Louis Stewart, and Frank Sibbald, followed the same route to the Saskatchewan but then travelled up the Cline River to Pinto Lake, over Cataract Pass, over Jonas Pass, and then to the Sunwapta River. They then travelled all the way north to the Miette Valley. Realizing that they had gone to far north they backtracked to the Whirlpool River and finally reached Athabasca Pass. But the highest mountain he could find nearby was only about 2800 metres high. Disappointed he wondered, "What had gone wrong with these two mighty peaks that they should shrink seven thousand feet in altitude and how could anyone, even a botanist like Douglas, make so monumental a blunder?" Coleman did not return to the Rockies again until 1902. After again beginning at Morley, they followed their old trail to Brazeau Lake. Quincy Coleman completed the first ascent of Mount Frances and the group attempted to climb Mount Brazeau before returning to Morley. Arthur Coleman then became focussed on Mount Robson. He had spent several years searching for the legendary Mount Brown and Mount Hooker only to find that a mistake had been made. Understandably, he was concerned that Mount Robson, which it was claimed rose over 3000 metres above its base, might be grossly exaggerated as well. In 1907, together with George Kinney, he left Lake Louise, travelled over and Wilcox Pass (where he has a chance meeting with, and was photographed by, Mary Schaffer) and after struggling through burnt timber and wilderness for forty-one days reached the base of the mountain. Unfortunately the weather was bad and, as they were too late in the season, it was only possible to explore the base of the peak. They exited the mountains via the Athabasca Valley. Rev. George Kinney and the Colemans returned to Mount Robson again in 1908, this time beginning their trip in Edmonton. After two attempts to climb Mount Robson were abandoned in bad weather, Kinney set out on a solo attempt on September 9th, overnighting in bad weather and reaching an elevation of 3200 metres before avalanches drove him off the mountain. The following day they reached 3500 metres in fine weather before retreating. Arthur Coleman never did climb the mountain but George Kinney returned the following year and is thought to have reached the summit ridge of Mount Robson. Both were present as part of the Alpine Club of Canada's expedition to Mount Robson in 1913 when Conrad Kain led a party to the summit. While in his eighties, Arthur Coleman made his last visit to the Rockies as part of the ACC's camp at Mount Fryatt. Coleman’s primary geologic interest was glaciers, and he travelled the world gathering data and photographs. He was also a prolific artist and painted mountain scenes. A water colour of Mount Robson was likely completed during one of his exploratory visits during a period of bad weather. In the painting the details of the mountain are obscured by mist with the unmistakable outline of the peak clearly defined above. [The Mountains and the Sky –Glenbow] Arthur Coleman is honoured by Mount Coleman above Sunset Pass in the Saskatchewan Valley, Coleman Lake, a high, hidden lake to the north of the mountain, and Coleman Glacier in the Mount Robson area. Mount Quincy in the Chaba River area of Jasper National Park was named after Arthur's brother Lucius Quincy Coleman. Arthur Coleman's book, "The Canadian Rockies, New and Old Trails" tells the story of these marvellous explorations and is a classic of Canadian Rockies Literature.