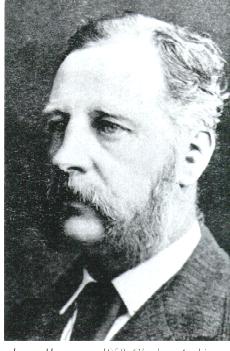

James Hector in 1858 (Courtesy Glenbow Archives NA 659-62)

Sir James Hector

(1834-1907) James Hector was a geologist, naturalist, and doctor who accompanied the Palliser Expedition. He graduated from medical school at Edinburgh University but also took many courses in natural science. One of his professor, James Hutton Balfour (see Mount Balfour), noted his enthusiastic nature, physical stamina, and endurance as well as his capable scientific attributes and recommended him to Sir Roderick Murchison, the president of the Royal Geographic Society (see Mount Murchison), for the position of geologist/naturalist with the Palliser Expedition. In August of 1858 the expedition reached the Rockies and at this point John Palliser divided his party and Hector was told to explore whatever areas appeared to be, geologically, the most interesting. Eugene Bourgeau accompanied Hector farther up the Bow Valley (Bourgeau only went as far as present Day Banff), guided by Peter Erasmus and a Stoney Indian guide who Hector referred to as "Nimrod" because he could not pronounce his Indian name. Hector was delighted to be in an area with cliffs and gorges where the rocks could be studied. His attempts to study geology as the expedition crossed the prairies were frustrated by the thick layer of glacially deposited clay. The party left the Bow Valley and travelled through Vermilion Pass (now traversed by Highway #93) and followed the Vermilion River to its confluence with the Kootenay River. Hector then travelled up the Kootenay Valley and over the low pass to the headwaters of the Beaverfoot River. He then followed the Beaverfoot to its confluence with the Kicking Horse River near Wapta Falls. The party then ascended the Kicking Horse River and passed over Kicking Horse Pass. At this point the group turned just before reaching what would become Mount Hector, and traveled north past what George Dawson would later name Hector Lake to the headwaters of the Bow River. After traveling down the Mistaya River, Hector reached the North Saskatchewan River and after some explorations in that area traveled down the river eventually reaching Fort Edmonton. The mountain portion of this amazing journey, at a time when there were no trails and when finding food was a significant problem, was completed in only thirty-eight days. During the following winter he continued his explorations in what is now Jasper National Park, ascending the Athabasca River with the intention of traversing >Athabasca Pass. Unfortunately his guide, Tekarra, had injured his foot, and without a guide Hector decided not to attempt the pass. He did, however, travel up the Athabasca to the vicinity of Mount Kerkeslin and Mount Christie before returning to Fort Edmonton. During the summer of 1859, Hector travelled up the Bow River for a second time, continuing past Castle Mountain, up the Pipestone River, over Pipestone Pass to the Saskatchewan, up the Howse River to the Freshfield Glacier, and over Howse Pass to the Columbia Valley and eventually to the Pacific. Peter Erasmus was a guide with the Palliser Expedition and spent considerable time with Dr. Hector. In his book, "Buffalo Days and Nights," Erasmus wrote that, "Dr. Hector was a tireless worker. His capacity for endurance in any kind of weather was the talk of men around camp. He had four horses to his string and they were not too many for his demands. There was no let up in his persistence, as day after day, all except Sunday, he continued his unending labours to cover as wide a range of territory as possible." Regarding Dr. Hector's personality, Erasmus wrote, "His handshake was firm and he had a hint of strength that captured my interest immediately. He had an affable, easy manner of conversation with any person he was speaking to. A thoroughly pleasing personality that had nothing of that assumed superiority or condescending mannerism that I was beginning to associate with all Englishmen of my narrow acquaintance. I like the man at once and nothing in my experience on the expedition or elsewhere ever changed this good opinion. Mount Hector and Hector Lake were named for Dr. Hector but Kicking Horse Pass was named for a horse who kicked Dr. Hector. As the party was struggling eastward towards the pass, one of the pack horses, in an attempt to escape the fallen timber which made traveling so difficult, plunged into the river. Hector described the events that followed, "...the banks were so steep that we had great difficulty in getting him out. In attempting to recatch my own horse, which had strayed off while we were engaged with the one in the water, he kicked me in the chest, but I had luckily got close to him before he struck out, so that I did not get the full force of the blow." Hector's guide wrote, "We all leapt from our horses and rushed up to him, but all our attempts to help him recover his senses were of no avail... Dr. Hector must have been unconscious for at least two hours when Sutherland yelled for us to come up; he was now conscious but in great pain. He asked for his kit and directed me to prepare some medicine that would ease the pain." Hector's men thought it was appropriate to name the river in honour of the "Kicking Horse" and the pass above was assigned the name as well. Although Hector did not record it in his report, it is said that his men came to the conclusion that he had been killed by the horse's kick and had dug a grave for him. He was almost buried alive and since he had not recovered his ability to speak, had to wink an eye to demonstrate to his party that he was still, in fact, alive. Even without Hector's injury, the party was having great difficulty finding food and was near starvation. They struggled towards the pass, eating blueberries along the way until they reached Wapta Lake at the summit where they camped and were able to kill a grouse and, "were happy to boil it up with some ends of candles and odd pieces of grease, to make something like a supper for the five of us after a very hard day's work. The next day a moose was shot and the men began to regain their strength. James Hector's detailed geologic work during his time with the Palliser Expedition resulted in the first description and explanation of the geological structure west of the Great Lakes and formed the basis for future work. George Dawson, himself a scientist renown for detailed work, referred to Hector's work as providing, "the first really trustworthy general geological map of the interior portion of British North America." He continued to make significant contributions to geology, particularly in New Zealand, and was knighted in 1887. Peter Erasmus was Hector's guide during his time in the Rockies. In his book, "Buffalo Days and Nights," he describes how Hector was admired by his fellow travellers for more that just his scientific abilities. "Dr. Hector alone of all the men of my experience asked no quarter from any man among us, drivers or guides. He could walk, ride, or tramp snowshoes with the best of our men, and never fell back on his position to soften his share of the hardships, but in fact gloried in his physical ability after a hard day's run to share in the work of preparing camp for the night, building shelters from the wind, cutting spruce boughs, or even helping get up wood for an all-night fire. He was admired and talked about by every man that travelled with him, and his fame as a traveller was a wonder and a byword among many a teepee that never saw the man." Following his time with the Palliser Expedition James Hector became head of the Geologic Survey of New Zealand and was knighted. In 1903 he returned to Canada with his son Douglas, hoping to visit the site where he was kicked by the horse and to cross Kicking Horse Pass by railway. Mary Schaffer met Dr. Hector at Glacier House in the Selkirks as he was travelling to Kicking Horse Pass. She overheard him mention to the lady behind the desk that he was going to, "his grave." Mary quotes his explanation to her as follows, "My own saddle pony had anything but a gentle disposition and he hated fording rivers, specially the kind this one was. I was having a good deal of trouble with him at one point, and finally went up behind him with a stick. I saw his heels fly up and then knew nothing more for hours. When I regained consciousness, my grave was dug and they were preparing to put me in it. So that's how the Kicking-horse got its name and that's how I came to have a grave in this part of the world." Schaffer went on to refer to him as, "A delightful old gentleman." Sadly, the morning after his conversation with Mary Schaffer Hector's son became ill. He was diagnosed with appendicitis and taken to hospital in Revelstoke where he died. Hector returned immediately to New Zealand and never returned to the Canadian Rockies. [Additional Information: Spry, Irene M. "The Palliser Expedition". Toronto: Macmillan Co. of Canada Ltd., 1963] [Additional Information: Beck, Janice Sanford, "No Ordinary Woman -The Story of Mary Schaffer Wilson"